Capturing a lot of headlines this week was news that the National Association of Realtors had reached an agreement to settle the massive lawsuit over the way real estate agents get paid. Many news outlets framed the story in the form of a question: Will a settlement reduce the prices of properties on the market?

That’s certainly a valid question to ask. Prices continue to climb as the demand for homes continues to outpace the inventory of homes on the market. After all, if you’ve taking a new job somewhere else, you need a new home. If your family has experienced a birth, a death, a marriage or divorce, if a member of your family has gone off to college, you likely need to upsize or downsize. Demand remains strong.

On the other side of the scales, inventory remains tight. Hiring conditions have thawed and employers have (perhaps begrudgingly) increased wages since Covid eased, and consumer prices have gone along for the ride. That means inflation. As a result, the Federal Reserve Board of Directors has raised interest rates several times in 2022 and 2023 as a means to contain rising prices. That’s meant that many homeowners who may want to sell up and move — but don’t really need to — are staying put. The 2% interest on a mortgage refinanced during the height of the pandemic is proving to be a heavy anchor. So supply remains very limited.

As long as those conditions remain, the answer to the question about the NAR settlement agreement is a simple no. The amount of money changing hands in any given transaction will stay about the same. So what was that lawsuit all about?

The legal action centers on how real estate agents are paid for their services. Typically — until now — an agent and a homeowner agree on a commission when the agent is contracted to sell a property. That commission, often 5% or 6%, is split between the seller’s agent and the buyer’s agent, with brokerages on each side often taking a cut.

It’s a system that works.

The seller’s agent quarterbacks the effort to sell the property, coordinating with lawyers, contractors, stagers, cleaners and others; schedules showings and open houses; makes sure all paperwork is properly filed and that deadlines are met; and counsels the sellers regarding price and negotiations.

The buyer’s agent finds suitable homes for clients, accompanies clients to showings and open houses, counsels buyers about offers and terms beyond the dollar amount, and like the seller’s agent, is responsible for proper paperwork, meeting deadlines and coordinating with an equally diverse cast that also includes lenders and home inspectors.

The portion paid to the brokerages goes toward office space, support staff pay, stationery and copiers, marketing and just about anything else that comes into play, right down to making sure fresh coffee is at the ready.

So what’s the problem? It’s that commission amount that goes to both sides. In reality, it’s just another line item in a complex transaction that has both sides paying for a slate of expenses that include legal fees, taxes, title costs, pro-rated utility bills, inspections and, of course, the actual price of the home itself.

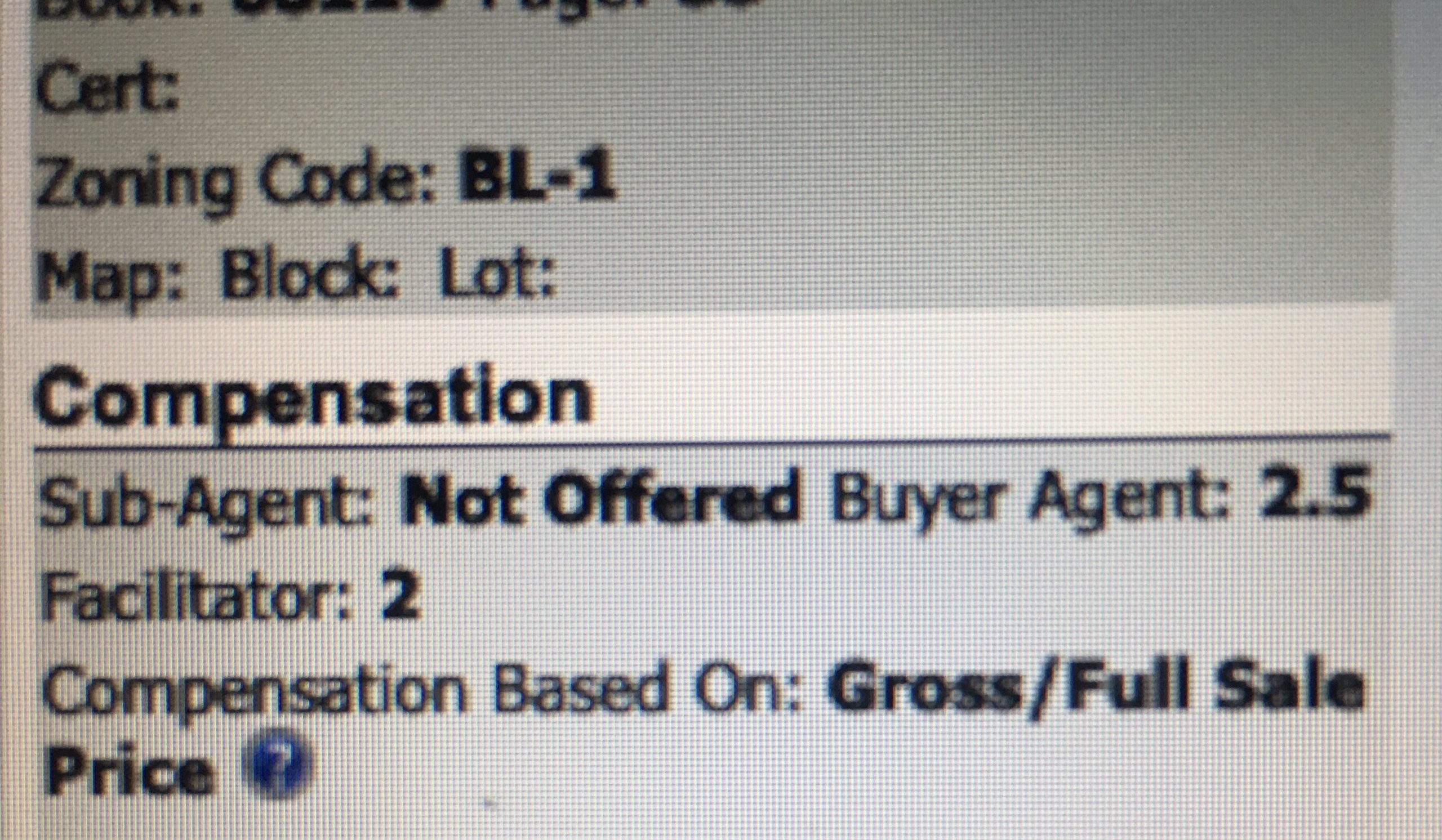

Most homes appear on the rolls of a multiple listing service — sort of an online database of properties for sale or rent, used by licensed real estate professionals. There’s a single line that shows what the buyer’s agent is to be paid when the sale closes.

The Department of Justice argues that, because that amount is visible to buyer’s agents, it can mean that homes with a low commission will not be shown to buyers. It’s like saying that an agent will only show $1 million homes to clients because they come with jumbo commissions. Sounds like a problem, but in reality, any good agent will want to find the right homes for clients. The commission amount is not a primary consideration, and agents can negotiate with buyers to make up the difference if there’s short money coming from the seller side.

There are other points in the lawsuit that seem like a reach: in some areas, key safes can only be accessed by regional Realtor board members, and some agents could mislead buyers into thinking their services are “free.”

On the other hand, putting limits on key safes is sound policy. If you’ve ever had your parent’s home broken into after their death (I have), you’ll see the need to restrict access to key safes to licensed professionals sworn to act ethically. And the “free” services argument falls down when you consider that any good agent will explain exactly how the transaction works.

Some sellers may argue that they’re paying for the opposition by paying the full commission. But as stated, there’s a lot that a buyer’s agent does. The main benefit to the buyer may well be to make sure the transaction isn’t derailed by a buyer without representation who fails to meet deadlines or causes different problems that would be headed off by a professional agent.

And that’s why this lawsuit won’t have much impact on the amount of money a seller walks away with. Buyers will still come with the same amount of money, but some will be paid to their agents directly, instead of going through the seller. The remainder goes to the seller, who still pays the commission to the seller’s agent.

Ultimately, the only ones getting a windfall are the lawyers handling the case.

(The opinions stated in this article are my own and do not necessarily represent Coldwell Banker, its management or any other person.)

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link